Piercing the Artificial Heart

Hello. Today’s post, I think, will be a Turing Test for the reader. If you find it to be interesting, entertaining and yet still somewhat disquieting, you are probably human. If you find it to be same-old-same-old, ho-hum common-knowledge among your brilliant, jaded peers, you are likely some sort of advanced data processing unit, or what I like to call, with a nod toward our ancestors, an “infernal machine.”

Look at the photo mock-up above. You saw it here just a few days ago, in this very spot. It was the top-of-the-page illustration of a previous Gene Pool, illustrating a winner in the most recent Invitational contest. Asked to make humorous predictions for the events of 2025, reader Leif Picoult wrote in: “Taylor and Travis finally marry in a simple ceremony on the moon.”

The image was created by an Artificial Intelligence imaging tool, in response to my request for a composite photo expressing the concept: “Taylor and Travis marry on the moon.” I didn’t even bother checking to see if there was already such a piece of human-produced art available on the Web, because I knew there wouldn’t be. The response to my AI request took three seconds. AI gave me four images from which to choose, including the one above. It was available for free, part of a service supplied by Substack to its writers. AI has progressed to a state of the art where it seems at least superficially slick and professional. Like Taylor and her beau.

I had dutifully labeled this image as AI-generated, and so I got some blowback from readers, and even from two professional colleagues of mine. They felt I shouldn’t be using AI, that it is undignified, and that the use of it made them … uncomfortable.

So, naturally, a couple days later I did it again, with this image, illustrating the concept of “a basket of deplorables.”

Then I got some more blowback from readers.

I have decided to examine this contentious issue further, and try to keep an open mind. We do so below. You might be surprised by the results.

But first, a Gene Pool Gene Poll. Remember, this is only about AI as applied to generating images for commercial use. I will address word- and research-based applications in a separate post, soon.

—

I think the first question to address is the most philosophically interesting: Does the whole thing seem, somehow, kinda … unseemly? Is it artistically lazy and sleazy, presenting an image as part of your own work that is not only not your own work, but the work of a stack of microprocessors and semiconductors and whatnot?

I contend the answer depends on your definition of art, and of what “your own work” means. To me, this boils down to: Have you, the human, materially contributed to this art?

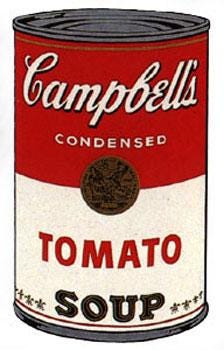

If you buy an original Warhol, you are not just buying the cost of his time, and paint, and canvas, and the skill of his brushstrokes and choice of colors. You are also paying — sometimes in enormous proportion — for his ideas, for his concepts that drive the art and give it added value. For example, Warhol’s epic, seismic choice to challenge the notion that there is a hard line between commercial design and fine art. The idea was the thing.

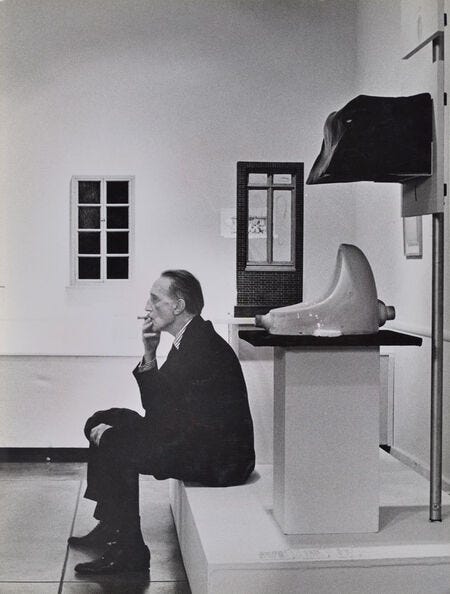

Similarly, Duchamps did NO actual work on his most famous and influential piece of art. He found it; it had already been designed and constructed by another. He gave it a confused title. He signed a made-up artist’s name to it. Then he physically lifted it (give him some credit; porcelain plumbing is heavy) and he laid it on a table in a gallery. Yet, this Duchamps piece is said to have been the Art that changed the concept of Art forever. Art can be a thought. Or something you pee into, dully, unthinkingly, unaware of its lines and curves.

So, where does AI come in here? Most AI-rendered images, I contend, represent an artistic collaboration by a human with a machine. In the case of Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, the collaboration is between the machine and Mr. Picoult, who came up with the comedic concept — one that to my knowledge had not before been articulated. The resulting artwork is a bona fide alliance. I was an enabler, merely — a curator, if you will — unlike Leif, who is a significant partner in this process even if he didn’t know he was creating visual art (which he didn’t). Do not fall for the Intentional Fallacy.

I believe that artistically, there is no problem here. I rest my case on Leif Picoult and Marcel Duchamp, two people whose names have never before, to my knowledge, appeared in the same sentence.

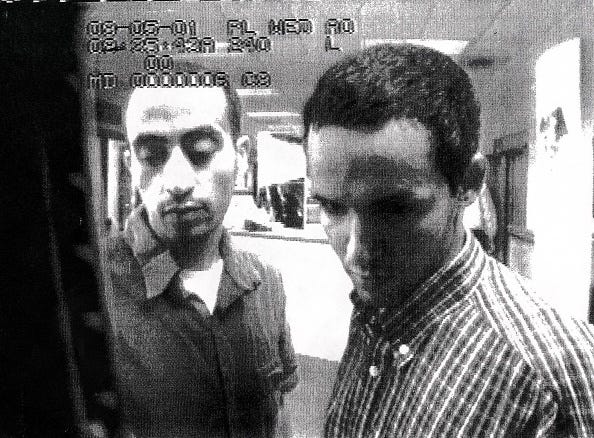

I confess a certain bias in the matter. I am the journalist who proposed, seriously, that the Pulitzer Prize for Deadline Photography in 2002 go to a machine: The ATM camera that caught these two guys withdrawing a few hundred bucks the day before 9/11. They were Hani Hanjour and Majed Moqed, pilot and muscle, respectively, on the flight that hit the Pentagon.

—

Issue number two is the more germane: Is it ethically unacceptable, a betrayal of professional artists and photographers, to use AI as a tool to accompany or illustrate a commercial work, an image that they or others like them might otherwise have been contracted to do? Might those people justifiably feel that such decisions are cold and mercenary, and — more important — that they result in an overall degradation in the overall quality of all published images, existing both as an insult to art and a threat to their individual livelihoods?

My initial reaction is: Maybe. But is there a pragmatic alternative? Has this not always been an inevitable hiccup resulting from the collision of form and function, progress and commercial realities?

Colorful, noble crafts have always been made obsolete by technology. You will likely never see a new bridge as lovely as this one:

Or, for that matter, a car like this.

But this is not an artistic argument so much as a moral one. Is use of AI graphics betraying talented artists everywhere? That’s a serious question, and it may be the one you all had in mind when you said my use of AI was harshing your mellow. It’s harshing mine, too — I know that however good my ideas will be, the results I get from AI will never be as brilliant and as those cartoons I was regularly able to order up from my cartoonist friends, back when a giant, rich corporation paid the bills — artists like Bob Staake or Eric Shansby or Alex Fine.

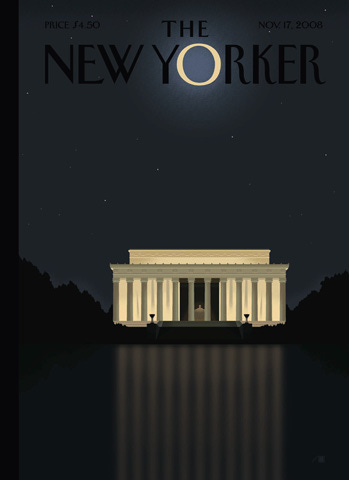

This was Staake’s elegant, ingenious cover from The New Yorker, conceived and drawn the night Obama defeated McCain.

I emailed Bob yesterday, and asked what he thought of the whole AI issue. He wrote back:

“I have plenty of illustrator/cartoonist friends who are understandably in a panic regarding AI — and they should be as the use of it by publishers directly threatens their ability to survive as artists. While I get Google alerts all the time about examples of AI art “done in the style of Bob Staake,” when I look at them I see very little resemblance to my work, and so I don’t feel as threatened so much as I do insulted. The problem that professional artists have with AI is that it learns by “studying” their previously published work - with no compensation being paid to the artist. They view this not as “creative inspiration” (we human artists have always been influenced by the work of our peers) but as outright theft.”

—

I also emailed my first cousin, Margaret S. Nakamura, who is a freelance commercial artist in New York City. The process of dehumanizing artwork, she said, was going on a long time before A.I, via editing tools that clean up human-submitted work.

Margaret said these computer-assisted images come out “so perfect and precise that they’re downright cold looking-- fine for scientific and technical drawing, not so much for other kinds of artwork..But at least there’s still a sense that a human mind and hand have controlled the stylus or mouse.

“A.I. is a whole different bailiwick—but probably more cost effective for companies, once they make an initial investment. And, the final publication will be entirely or partially digitized anyway, and likely viewed on a tiny phone screen; so the fact that the artwork was created by A.I. might not be apparent to a viewer. From a company’s perspective, why deal with pesky artists who demand more time and money for the same job, then? So yes, very frightening.”

Or as her artist-husband Hideaki Nakamura put it, far more succinctly : “Commercial artists will disappear.”

—

And what about photography? Same story. I will never get, from AI, images to compete with those by my vastly talented photographer friends like Michael S. Williamson, Carol Guzy or Murry Sill.

I first met Murry at The Miami Herald in the early 1980s. At the time, he instantly became the bravest person I’d ever known. While covering the civil war in El Salvador in 1981, he took this photo during a firefight in the streets. The crouching man with the camera around his neck was French freelance photographer Olivier Rebbot, on assignment for Newsweek. A moment after this photo was taken, Rebbot half-stood to get a better look over the wall, was was fatally shot in the chest. Murry had been 20 feet away.

After Murry retired from The Herald, this war photographer decided, with characteristic eccentricity, to become a middle-school science teacher on Miami Beach, where he continued to take photos with shrewdly, almost mathematically perfect, human-infused design and composition:

I would have emailed Murry for his thoughts on this issue, but I couldn’t. It turns out he died two years ago in a bicycling accident in Florida, at 68.

To quote Joni Mitchell, sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.

—

To sum it up, I am still thinking about this issue. It’s not quite as simple as I’d imagined. I will think more and report back.

—

Your second Gene Pool Gene Poll:

—

As always, please send your Thoughts, Observations And Such Things into the TOAST button below:

—

And finally, before I get to your mercifully short group of questions and observations, a nakedly manipulative plea from me. The Gene Pool is 99.9 percent AI-free. It is wholly owned and operated by humans. The only fully AI-generated image in this very post is the one that follows, which is what it offered me when I asked the AI tool for an image representing the single, one-word, entirely open-ended concept of “something.”

See? Get it?

No?

Neither do I. DO YOU SEE WHAT I AM SAYING HERE? Send me money, to save humanity.

—

The Q and A’s I responded to below were received before 9 p.m. on Monday. Please send in more, and I will address them in a day or two.

Soon, probably tomorrow, I will be doing PART II of “Piercing the Artificial Heart.” It will be an illuminating discussion of AI and … humor.

—

Q: Youtube has a few final radio broadcasts from nations right before their occupation by the Nazis. In my opinion, the Greek message is by far the most powerful. Be sure to turn on English subtitles if you don't speak Greek. The nation was about to fall to a fascist regime, and with it any freedom of broadcast. But on their way out, and presumably into capture, or into hiding, they had one powerful message for their citizens - "In just a few moments, this station will not be Greek. It will be German. And it will broadcast lies. Do not listen!" What courage it must have taken that broadcaster to say that over the airwaves as the Nazis were marching into the city. But it was the right thing to do. As Trump threatens censorship of the media, which no doubt will get even worse once he becomes President, will anyone have courage to send a similar final message before it is too late?

A: As you say, this is powerful. Don’t just listen to the voice. Listen to the timbre of the voice. The terror, and the strength.

Q: Regarding your video of the drunks trying to mount a fiberglass horse: This act could hardly have been done better by a team of choreographers and stunt doubles with weeks of planning. In sober life, this man would not have been capable of it. Look at him! Feet over head! He is not a gymnast, sober. He was that night. This video is about what we ordinary humans can become, if we try: Stupid and beautiful and awesome. It also contains real danger, which movies do not. Yes, Tom Cruise hangs onto planes 5000 feet in the air for real, but we know we will not see him get hurt. This video keeps defying actual tragedy. We are in awe, and relieved, and laughing. And nobody MADE this. This is just life we are lucky to witness.

Okay, this one was made. But it is a rarity: A superstar actor with the physical skills of an acrobat:

Robert Downey Jr. as Charlie Chaplin.

A: This should be seen right now. Three minutes of genius.

—

Q: Your commenter’s story of hearing the boss's voice on the radio reminded me of one of the most surreal moments of my life, which occurred about 20 years ago. My alarm went off at 6:15am and I stumbled, bleary-eyed, into the bathroom to take a wake-me-up shower, as I did every morning. I got in the shower and switched on the shower radio and... MY MOM'S VOICE filled the room. Being half-asleep, I was VERY confused. I was like... did I call my mom somehow?? Why???? Turns out she was interviewed on NPR and I happened to turn the radio on at the exact right moment.

A: Excellent.

—

Q: Gene, after recent re-review, I agree Sinatra's "The House I Live In" video is rather naive and superficial, but then so am I. Anyway, I first saw the film while a kid at P.S. 18, Franklin D. Roosevelt Elementary School in Baltimore and recall it with great affection. I had some wonderful memories from my youth and from P.S. 18. I was a member of the school's safety patrol until I was dismissed for building a snowman while on duty outside one wintry morning. Currently, I am considering appealing that decision.

— Howard Walderman

A: Hey, Howard. I still cannot forget the moment in 1987 when I and my family moved to Cambridge, Mass. for a fellowship year at Harvard. My kids had grown up in Miami, and had never before seen snow. It came down heavily one day in late November, and I took them out in the front yard of the apartment house in which we were renting rooms.

We built a snowman. A little one, maybe four and a half feet high. Carrot, charcoal, a hat, the works. The kids — Molly was 6, Dan was 3 — were delighted.

The next morning, the building superintendent knocked on our door. The snowman would have to go, pronto. It was against Regulations. As you might expect, the kids took it with stoic maturity.

(No, they did not.)

—

Q: When I was a journalism major at Temple University in the late 1960s, we often used AI, but usually after work. Back then, of course, AI meant alcohol inebriation. It seldom improved our work, but it did sooth our mood after work. That AI was much better than the current AI.

A: Thank you. You have soothed my mood.

We’re done for the day. Please keep raising toasts.

In addition to the art theft and creeping laziness (to be followed by the inevitable acceptance of bad art as Normal), we have the energy use issue. This dreck uses a crapton of power. I fear it’s a losing battle, though.

Here’s my concern about AI, aside from the theft. Right now it’s appropriating from art created by humans. As it becomes more popular and ubiquitous, the sources available to steal from will increasingly be … AI. We will likely descend into a nadir of artistic homogeneity; humans will notice the problem but the monetary advantages of automation will weigh heavy against efforts to inject freshness.