On the Fritz

Hello, welcome to the Weekend Gene Pool, where I ask you to weigh in on an issue in return for entertaining you. The issue will come later, but first, the story.

When I was a young guy, I occasionally played the Lotto in Michigan. It was in the early years of lottery science, but it operated pretty much the same as today: You chose six numbers between one and fifty, and if you hit, you made a lot of money, though basically no one ever did, especially me.

Each week, I would use the same six numbers: 9, 19, 22, 23, 30, and 49. They were a superstitious choice, based on the only religion I ever had, worship of the New York Yankees. Those were the uniform numbers of players I always liked, sometimes for weird, inexplicable reasons, which I took as divine inspiration.

Nine was Roger Maris, my childhood hero. Twenty-two was a mediocre 1960s starting pitcher named Bill Stafford. Twenty-three was the 1980s superstar Don Mattingly. Thirty was the the Yankees’ elegant, acrobatic second baseman Willie Randolph. Forty-nine was the overpowering lefty pitcher Ron Guidry.

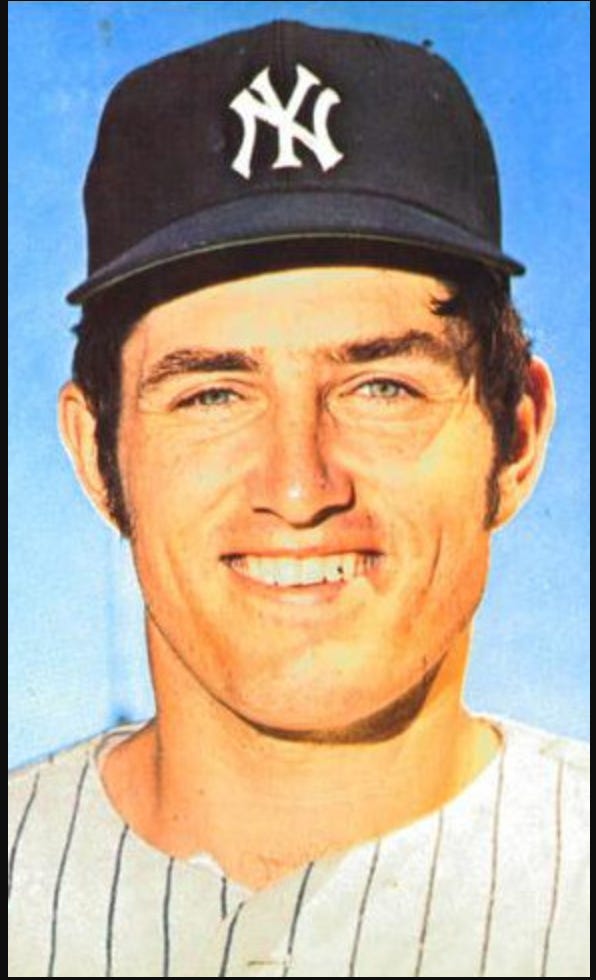

But 19 was the oddest choice. The number belonged to Fritz Peterson, a southpaw from the 1960s and 1970s who ended his career with a barely winning record (133-131.) He died on Friday at the age of 82, deep into Alzheimer’s. I want to memorialize him here, in this appropriately cheesy venue.

Fritz was a prankster. He once wrote a letter to the Yankees retired first baseman Moose Skowron on a fake letterhead from the Baseball Hall of Fame, asking Skowron to donate his heart pacemaker to The Hall after he dies. He also faked a letter on Yankee stationery asking third baseman Clete Boyer to participate in a drinking-to-the death contest against pitcher Don Larsen and third baseman Graig Nettles, all known tipplers.

I liked Fritz for that, but also for a more pertinent baseball reason: His stuff was unremarkable — not a broad or inventive pitching repertoire, below-average velocity, not much bite on his pitches, but he had one thing that made him competitive and (relatively) successful: absolutely fabulous control, or “location,” as the hacks call it. He could reliably hit the strike zone — the corners, mostly — to within a square inch of his target. The man walked almost no one. If you were going to get on base, you had to hit your way there. In a 12-pitch at-bat, Fritz almost always won.

To me, he epitomized the value of self-discipline. He might have been wacky, but he had self-control. It was a life lesson for me, at 15.

Then, something unbelievably weird happened. He and a pitching teammate, Mike Kekich, swapped families. Wives, kids, dogs. Mrs. Kekich became Mrs. Peterson. Mrs. Peterson became Mrs. Kekich. The dogs — Butch and Keister, as I recall, though I could be misremembering — changed owners. As did the kids. Not a sign of self-discipline.

This also taught me something that stuck with me: that you can’t really ever know someone, or make assumptions. It tickled me.

Today’s Question: Tell us a story about someone you thought you knew, but evidently didn’t. Send the story here:

There’s an interesting postscript to the Fritz Peterson story. Mike Kekich and the former Mrs. Peterson broke up almost immediately after the spouse-swap. But not Fritz and his new missus. They stayed married for 50 years. Susanne was at his bedside when he died.

So maybe his control never actually deserted him.

Finally, today’s Gene Pool Gene Poll:

See you on Tuesday.

100% of us know someone who is planning to vote for him, but apparently only 76% of us realize it or can bear to admit it.

Family and some lifelong friends who have lost their frickin' minds to trumpism.

I mourn.